Ahmad Khan Appointed Visiting Professor at Columbia Ahead of Publishing Monograph on Sunnism

“Students come to my courses with assumptions about what the Islamic tradition is and is not, and they go away with a broader horizon about the intellectual diversity of the Islamic world; an awareness of its community of interpreters who, generation after generation, refined and reshaped Islamic traditions; and an appreciation for the richness and complexity of the great classics of Islam in the realms of poetry, law, theology, Sufism and ethics,” said Ahmad Khan, assistant professor in AUC’s Department of Arab and Islamic Civilizations.

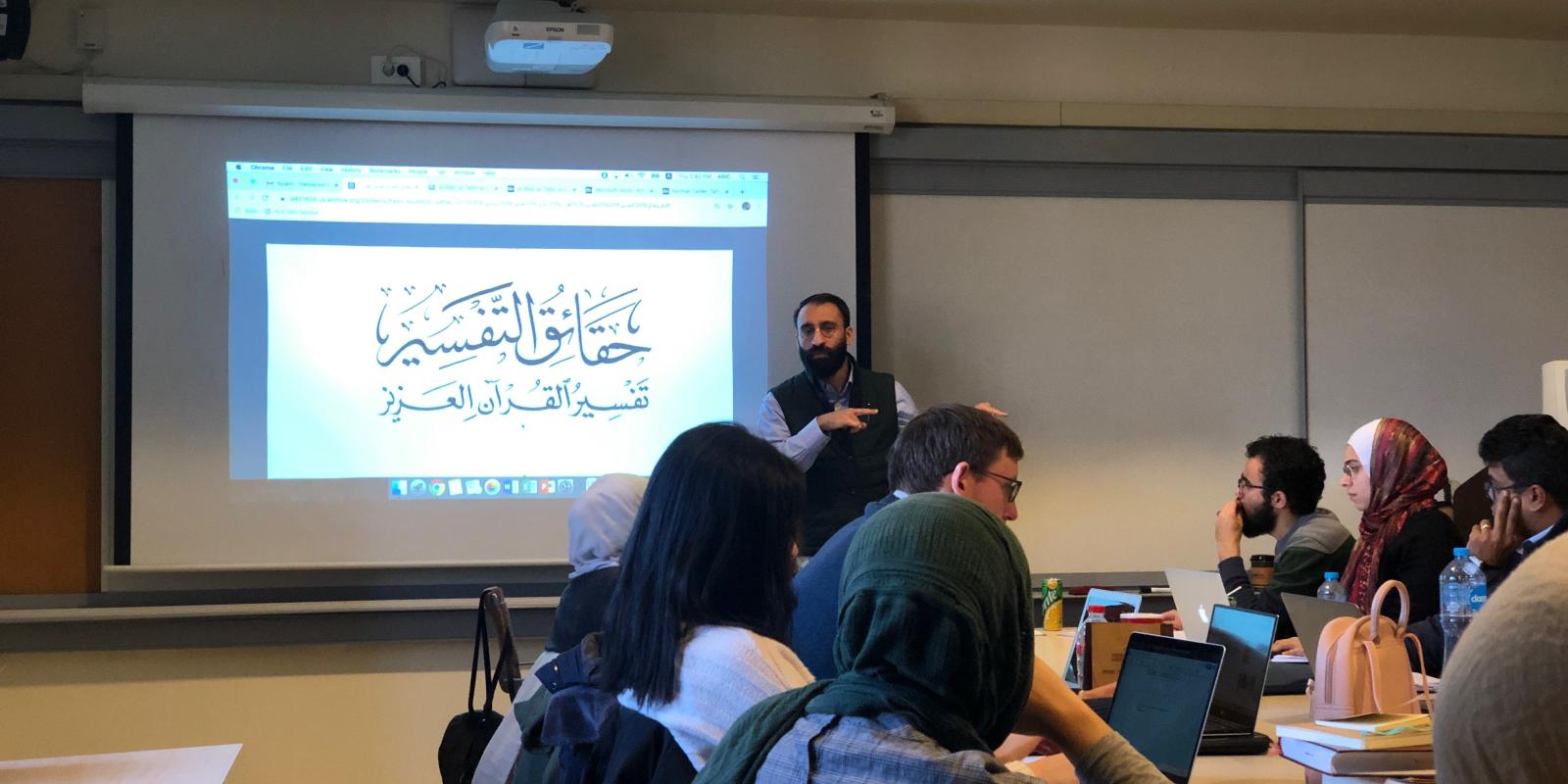

Khan has been awarded the Arcapita Visiting Professor at Columbia University for Spring 2022, hosted by the Middle East Institute and the Department of Middle Eastern, South Asian and African Studies at Columbia, where he is currently teaching the graduate course, Islamic Thought in an Age of Print.

“It is an honor to be awarded the visiting professorship,” Khan said. “The Arcapita Visiting Professorship has been a fantastic opportunity to think, research and write.”

Khan’s professorship is part of a long-standing and rich history between the two universities. Lisa Anderson, who served as AUC president from 2011 to 2016, and prior to that as AUC’s provost from 2008 to 2010, is currently dean emerita of the School of International and Public Affairs at Columbia. Furthermore, AUC’s current President, Ahmad Dallal, received his PhD in Islamic studies from Columbia.

“I hope to use my appointment at Columbia University to explore opportunities to strengthen the ties between these two universities,” Khan said.

Khan enjoys teaching at Columbia and AUC alike. In his classes, he introduces students to the great classics of Islamic civilization via texts in classical Arabic, exposing them to major thinkers of the Islamic world like Ibn Khaldun, al-Shafi'i, Rabi'a al-Adawiyya and Ibn al-Farid.

“The students at Columbia are in many ways like my students at AUC: bright, curious and dedicated to learning more,” said Khan. “Nowadays, much of my research is shaped by my teaching at AUC. The discussions we have are helping me examine important topics in the field of Islamic studies and civilizations.”

Delving into Islamic Studies

Khan’s research interests stemmed from the interdisciplinary training he received during his PhD at Oxford. There, Khan was able to take a variety of courses in history, literature, poetry, religious thought, and Arabic and Persian classical texts. This led to him having a holistic and diverse range of thoughts and approaches to Islamic studies, history, theology and literature.

This year, his monograph, Heresy and the Formation of Medieval Islamic Orthodoxy: The Making of Sunnism from the Eighth to the Eleventh Centuries, is the first major book in the field dedicated solely to the development of orthodoxy and heresy within Sunni Islam. The work examines conflicting efforts by Muslims during the eighth to 11th centuries, to define heresy and orthodoxy, finally giving way to a tolerant and diverse form of mainstream Sunnism. Khan looks at why and how Sunni Muslims, contrary to popular narratives, handled disputes over religious ideas often without recourse to violence. The book is expected to be published in December by Cambridge University Press.

“In this investigation of discourses of orthodoxy and heresy, we learn how medieval scholars and textual communities were engaged in constant and rapid efforts to develop an indigenous apparatus through which consensuses could be reached about orthodoxy and heresy; how orthodoxy was not a later ‘communal fiction’ but entailed stages and processes that can be identified and were identified by medieval Muslims,” said Khan.

“Above all, we gain insight into how a formidable medieval society and religion negotiated conflict and disagreement without giving birth to a widespread culture of imperial councils, inquisitors and persecutions,” he said.

By the 11th century, Abū Ḥanīfa, Mālik b. Anas, al-Shāfiʿī, and Aḥmad b. Ḥanbal were regarded as representations, par excellence, of medieval Sunni orthodoxy. “As such, the legal schools that coalesced around them became markers of medieval Sunni orthodoxy, and they spawned a religious tradition that is almost unparalleled in its relevance and longevity throughout Islamic history,” said Khan. “The book shows how orthodoxy and heresy in the eighth to 11th centuries may best be understood as processes.”

Working on this book also led Khan to study an array of medieval texts in Arabic and Persian. Many of these texts were edited and printed in the 19th to 21st centuries by modern scholars and editors in the Islamic world. He examined the processes by which these texts were transmitted in modern times, such as in Egypt, and how this helped shape the development of modern Islamic thought. This connection between his research on medieval Islam and Islamic thought in an age of print is explored further in the course Khan is currently teaching at Columbia.

The professor is also currently working on a book, Religion and Empire in Early Islamic Society, which discusses how Islamic law and its legal culture played a role in shaping early Islamic societies in regions like Iraq, Khorasan and Egypt, and is expected to be completed in 2023. Alongside these projects, Khan’s research includes the study of Quranic interpretation, the role of women in hadith learning, and Sufism.

The larger context of today’s society cannot be ignored when discussing Islamic studies. “The current sociopolitical context [of the global war on terror and sensitivities related to Islamic extremism] has resulted in major misrepresentations of Islamic traditions both from the inside and outside,” he said.