Shining a Light on Water Pollutants

Did you know that every type of bacteria has a unique light signature? Mohamed Swillam, professor and chair of the Department of Physics, is using this fact to identify different types of pathogens in Egypt’s water supply with new remote sensors designed by the professor and his team.

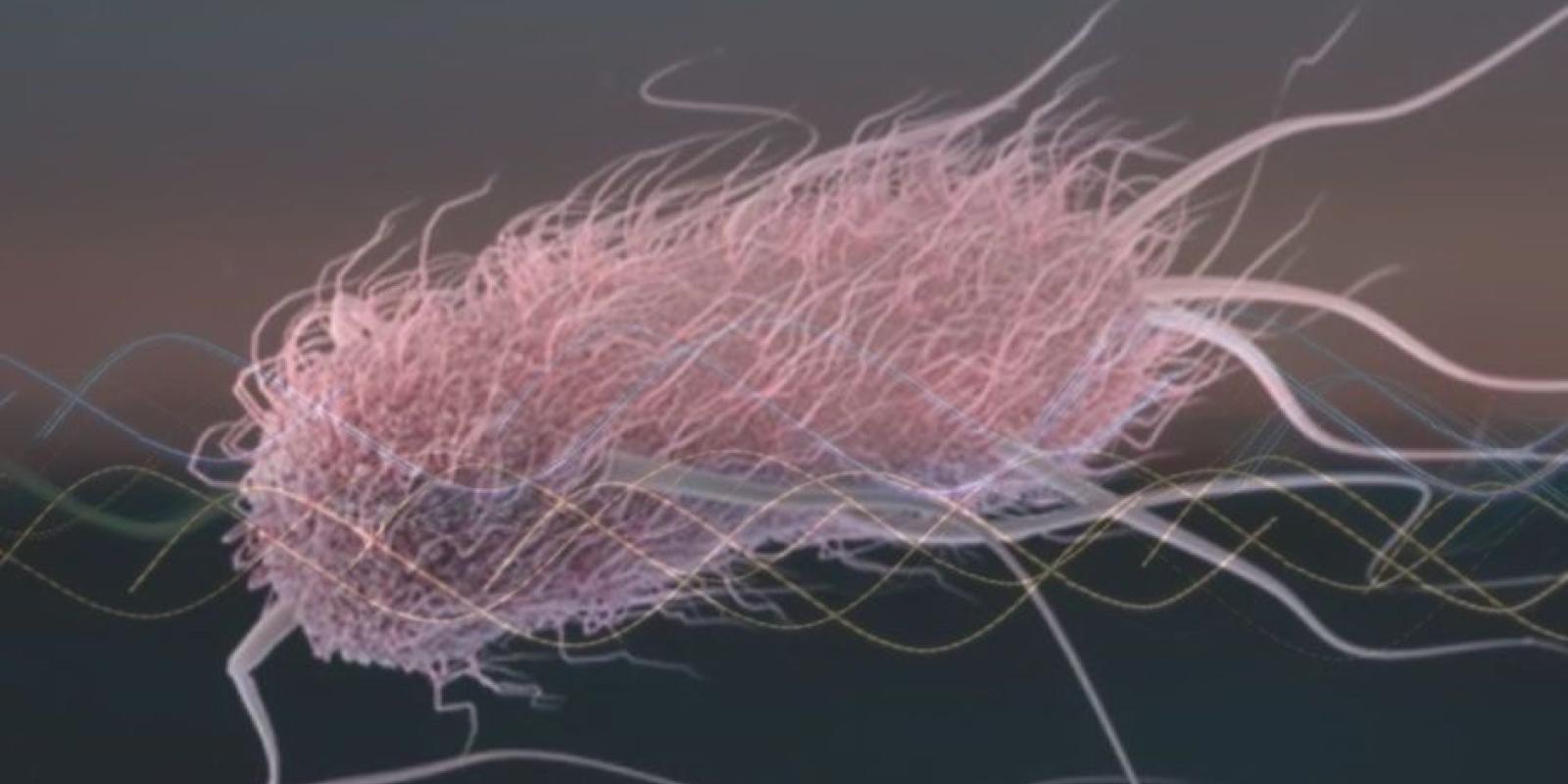

“We’re making portable sensors that can detect different bacteria in the water, like E. Coli and salmonella,” Swillam explains. “They can also report on the presence of heavy metals or water salinity.”

With a grant from the Conservation, Food and Health Foundation in the US, Swillam and his team are creating sensors that are designed to float in bodies of water, like rivers or canals, and transmit their reports wirelessly to a nearby data station. These reports will be analyzed in real time, providing a live map of contamination areas throughout the country. Such a map could help to improve food security by monitoring water quality and consequently, protecting crops. In the future, this data will be used to develop an artificial intelligence model capable of automatically identifying the best conditions for growth.

“The sensors can record salt concentration and pollutants in the water and transmit that information to farmers,” Swillam explains. “Then, the farmers can compare that to how the crops are either growing or dying and make necessary adjustments.”

In Action

The sensors develop the reports by taking a water sample, shining a light through the bacteria in the water and measuring how the intensity of the light changes. Each bacterium has a distinctive effect on light intensity, like a personal signature or a fingerprint, that sets it apart from other bacteria.

Ideally, each sensor will be fastened to a 3d-printed miniature boat which also houses a solar panel on top — used for powering the sensor. A small antenna will transmit the report and the boat’s location to a central data station. In order to get as much data as possible, Swillam hopes to release thousands of boats throughout both Egypt and Africa as a whole.

Improving Environmental and Physical Health

Moving forward, Swillam and his team, which includes students of biology, pharmacology, engineering and physics through SSE Dean’s research initiative, are hoping to develop the sensor in a way that can be used in all sorts of contexts, such as identifying illnesses in humans. He is currently working with funding from Pandemic Tech and the Academy of Scientific Research in Egypt to use this sensor technology to detect COVID-19. He is also working with AUC’s Department of Biology to identify the light signature of ovarian cancer in human urine samples. If the light signature of a virus or disease can be classified, then Swillam can adjust the sensor to identify it.

The sensor can also be used to identify emissions from cars in Egypt. With an Information Technology Academia Collaboration grant from Egypt’s Information Technology Industry Development Agency, the team is designing a small laser sensor that can identify pollutants and, similar to the water pollution sensor, create a real-time map of air pollution in the city. This will help compensate for the lack of widespread emissions testing of cars in the country.

Through his research on combating air pollution, water pollution and environmental health, Swillam’s work contributes to AUC’s Climate Change Initiative. In a ranking of scholarly output for the last year, Swillam placed second in Egypt in the field of electronics and optical materials, third in material engineering and fourth in condensed matter physics. A prolific researcher, his recent publication on technology that can sense all green-house related gasses was chosen as the editor’s choice in Nature.