International Day of Mine Awareness: Robots to Clear Landmines

April 4 is the International Day of Mine Awareness and Assistance in Mine Action, declared by the United Nations as a day for raising awareness about landmines and their impact worldwide.

With approximately 23 million landmines, Egypt has the highest number of landmines in the world and is the fifth country with the most antipersonnel landmines per square mile, according to landmine.org.

“The north coast is heavily mined from World War II, largely as a result of fighting that took place between Germany and Britain,” explained Maki Habib, professor in the Department of Mechanical Engineering and director of AUC’s robotics, control and smart systems graduate program. “This is a good region for development, but this development is being delayed because landmines remain in the region. The mines there are old and unsophisticated, so removing them would not require very advanced technology. However, the problem is that changing levels of sand cause the mines to be pushed deeper and deeper below the earth.”

Landmines and explosive remnants of war pose a threat not only to Egypt, but more than 80 countries worldwide. “Landmines are prominent weapons,” said Habib. “They are so effective, yet so cheap, and easy to make and lay.”

Demining Challenges

Humanitarian demining is a critical first step for reconstruction of post-conflict countries, Habib explained. The primary goal of demining is the total clearance of land from all types of mines and unexploded ordnance. “The important outcome of humanitarian demining is to make land safer for daily living and restoration to what it was prior to the hostilities,” said Habib, who established a concentration in mechatronics as part of AUC’s mechanical engineering program.

However, a number of difficulties plague the demining process. First, afflicted countries have landmines that date back to World War I. “Most of these countries do not have the economic infrastructure or logistics to organize for removing these landmines,” explained Habib.

Demining technology also has to account for issues with sensing mines. “Lands normally associated with landmines were usually part of a conflict, so there will likely be other exploded material fragments lodged in the land,” noted Habib. “This creates problems for basic metal detectors, as they will pick up on metal shrapnel and assume them to be mines. And this does not even touch on the issue of other types of mines, for example those with plastic or wooden casing where the triggers are very small pieces of metal. In sensing these mines, a metal detector wouldn’t work because the trigger is so tiny.”

Habib added, “There are about 1,000 false alarms to every one landmine detected. Humans have higher thresholds than current technology to identify mines, reducing the possibility of false alarms, but demining is incredibly dangerous to humans.”

Another challenge is that landmines can be literally found anywhere. “This means at the seashore, in agricultural land, under normal cities, in residential areas, in the desert –– you name it,” Habib said. “What kind of technology can accommodate all of these different terrains?”

And this is where the main issue lies: No one demining technology can work for all environments. “Clearing large civilian areas from anti-personnel landmines and cluster munitions is a difficult problem because of the large diversity of hazardous areas and explosive contamination,” said Habib. “A single solution does not exist, and many UN Mine Action participants have called for a global toolbox from which they could choose the tools best fit to a given situation.”

Robots to Clear Landmines

To address this issue, Habib has been working for the past four years as advisory board member and researcher in the TIRAMISU European project, which addresses the need for integrating different technologies to build a global toolbox for demining practices worldwide.

“The project aims to provide the foundation for a global toolbox that would cover the main UN Mine Action activities, from the survey of large areas to the actual disposal of explosive hazards, including Mine Risk Education,” said Habib. “The toolbox produced by the project provides Mine Action actors with a large set of tools, grouped into thematic modules, which helps them perform their jobs better. These tools are designed with the help of end-users and validated by them in mine-affected countries.”

One of these tools is the use of robots to clear landmines. “Robotization accelerates the demining process and avoids having deminers in direct physical contact with the mines,” Habib said.

Working in this field since 1994 and with the TIRAMISU project, which brings together international organizations and experts with extensive knowledge in the field, Habib has made advancements in robotics for demining. “Most countries afflicted with landmines are poor, and the technical know-how is not high. Lightweight and portable robots are the one type of technology that enables residents to use it easily, while at the same time keeping in mind the use of local resources in developing it,” noted Habib, whose work in robotics has not only helped in demining, but also aided the elderly and individuals with special needs.

Going Local

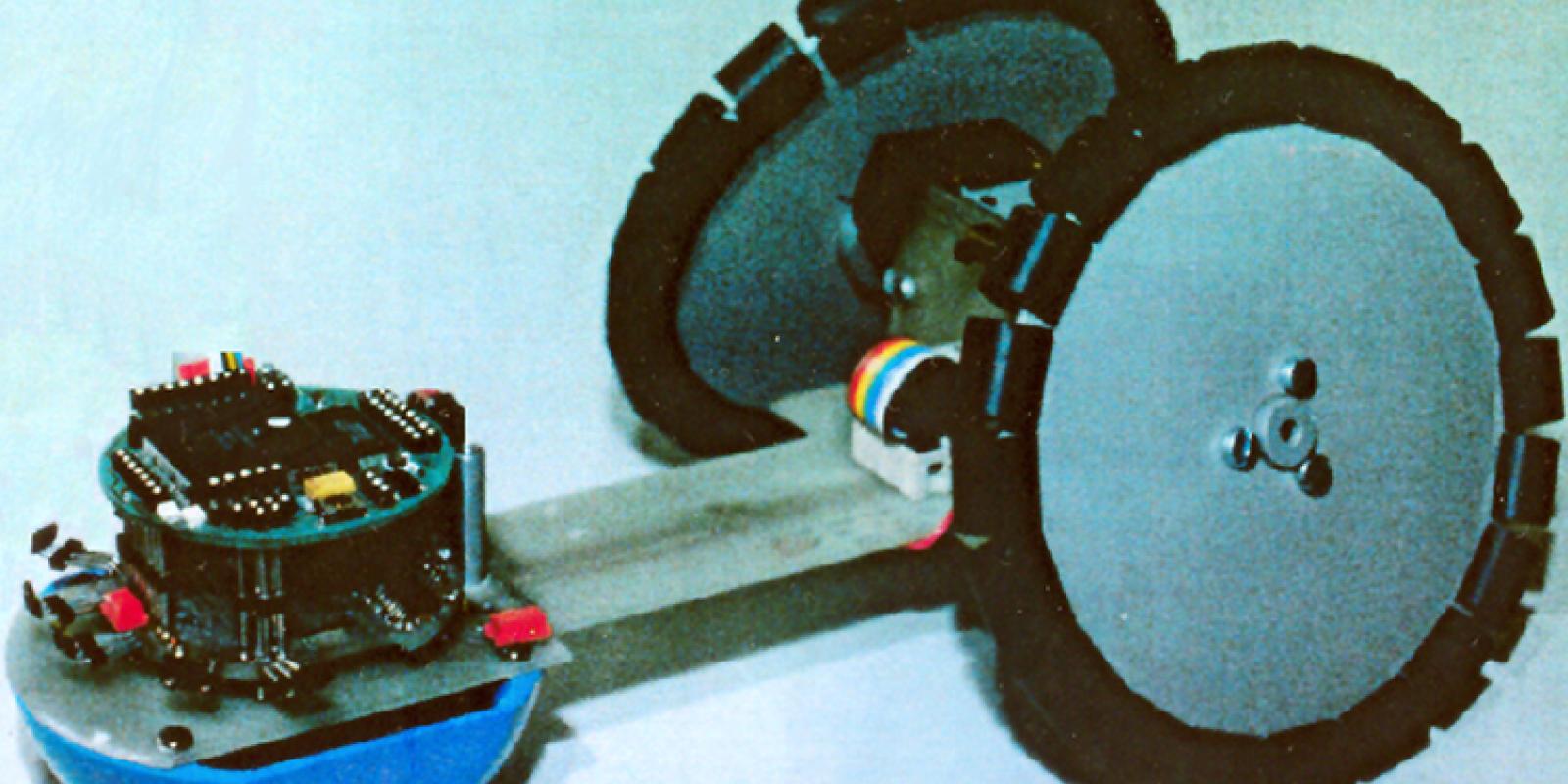

The first demining robot Habib helped develop was a multi-mode, low-cost mobile robot, PEMEX-B, with mountain bicycle wheels that could be adapted to local material such as bamboo or any suitable local resources. “Southeast Asia is one example where bamboo was readily available,” Habib indicated. “The bamboo wheels were considered for the PEMEX-B robot as a cost effective and alternate material available locally when the robot is subjected to damage due to explosion. Also, fabricating elements of the robot structure within the local environment of the mine field helps indigenous companies open job opportunities in the local market.”

In many developed countries, Habib explained, researchers have created highly logistical, expensive technology that not always works as required. “Any minor damage to these robots affects their efficacy, and maintaining them is difficult, so you end up losing a lot of money,” he noted. “That is why it is important to use inexpensive, local resources while properly protecting the sensing and decision-making components.”

Intelligent Robots

In addition to utilizing local resources, robots involved in demining must have “intelligent and flexible mechanisms,” Habib affirmed. “They must be able to learn from experience, their movements must be controlled, and they should have sensors to ensure safety. Sensors are the most effective tools supporting the robotization of the demining process.”

Demining robots must also have the capability to move through a muddy, sandy, rocky or grassy area, and even a forest. For that purpose, Habib developed navigation systems with obstacle-avoidance techniques that enable the robot to avoid obstacles blocking its path, navigate to effectively search the mined area in order to map any detected mine, ensure area coverage and communicate the necessary information as required. He also developed a heterogeneous, multi-robotic system that enables different robots to coordinate and cooperate in navigating mined areas –– searching, marking and mapping wide mine fields.

While no single country afflicted with landmines is currently declared mine-free, Habib’s work continues in an effort to build a global database of technology in the fight against destructive mines. “The tools we are devising represent a step forward in forming a unified, comprehensive and modular integrated solution for the clearing of large areas from explosive hazards,” he said.