A Warm Virtual Welcome: Class of 2025 Joins AUC

AUC welcomes the Class of 2025 in unusual circumstances — with new hopes and challenges awaiting them. AUC is still implementing a hybrid model of classes with an emphasis on maintaining a low-density campus.

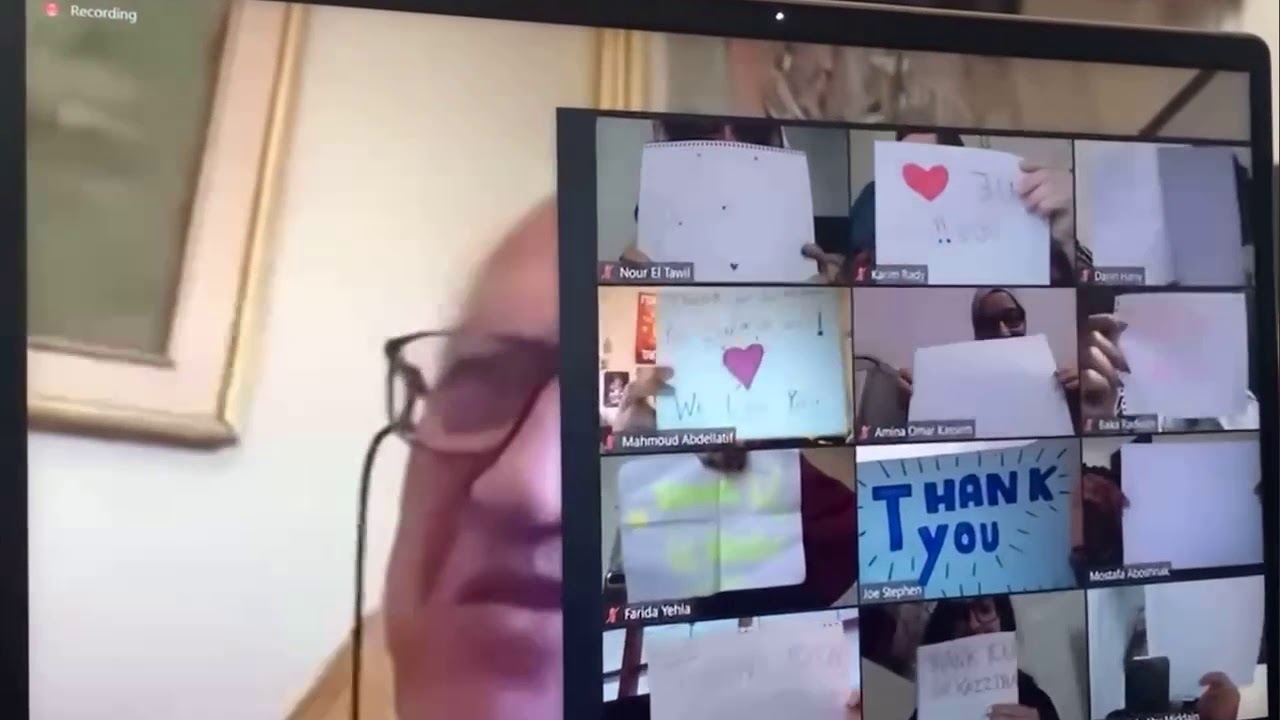

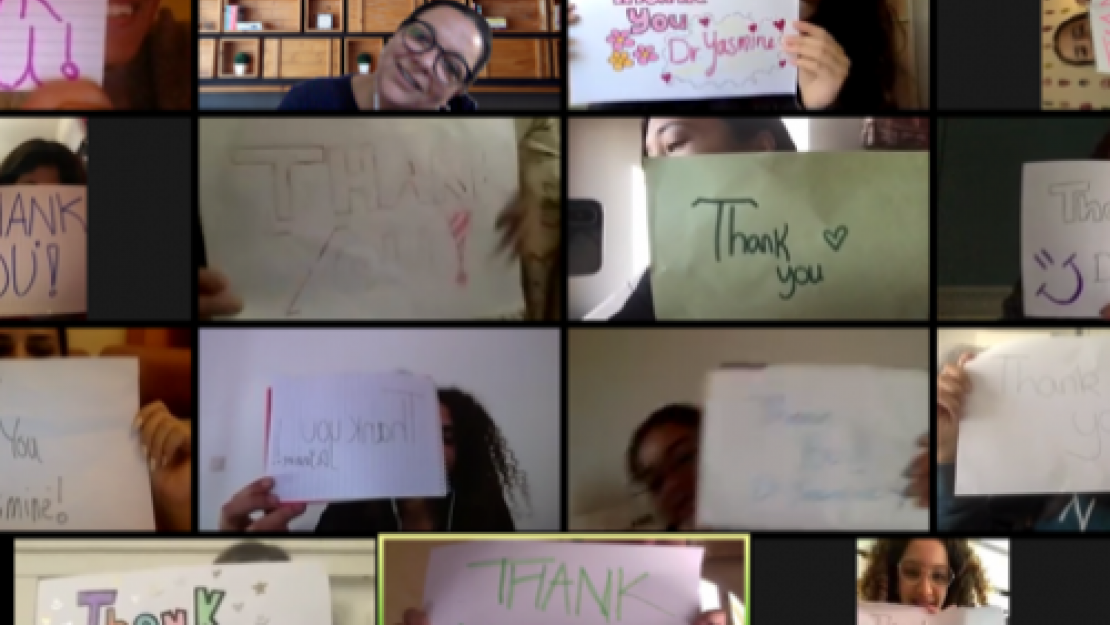

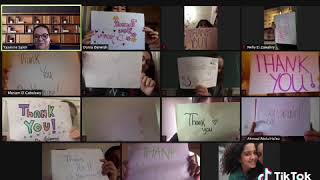

Having the first month of the spring semester entirely online did not prevent the incoming students from enjoying their orientation and preparing for their AUC journey.

"We are all ready for the pandemic to end and active life to resume on campus, yet for the ongoing safety of the community, we conducted this year's orientation entirely online via Zoom," said Mohamed Gendy, manager of the First-Year Program. "This didn't stop the new students from fully engaging with their peer leaders during the sessions — asking questions, exchanging ideas, sharing stories and playing educational games. The energy and vibes were great."

The new undergraduate class — 54% females and 46% males — enriches the community's diversity, with students coming from Nigeria, Algeria, Yemen, Iraq and Saudi Arabia.

Likewise, on the graduate level, the class — 70% females and 30% males — comprises a diverse international body coming from the United States, Nigeria, Libya, Yemen, Canada, Kuwait, Palestine and Syria.

Students expressed their hopes and eagerness to learn more about Egyptian culture, engage in a wide variety of cocurricular activities and improve their Arabic-language skills. News@AUC caught up with some Egyptian and international students during orientation week to learn about why they decided to join AUC and what they look forward to this semester. Here's what they had to say:

Amanda Robles, an international student, studying at the Catholic University of America in Washington, D.C., is looking forward to forming a strong base for Modern Standard Arabic and Egyptian Colloquial Arabic, in addition to acquiring a thorough understanding of the regions that practice those languages. "When it comes to subjects regarding the Middle East, [my home university] does not offer many options for courses," she said. "In comparison, AUC has an extensive list of courses which range from the culture of different areas in the Middle East to language, politics, and economics; this is why I chose AUC. I haven't seen a university that offers a list of courses as impressive as AUC, and since my university partners with AUC, I thought it would be an excellent option!"

Olivia Voss, an international student studying international relations at the University of North Carolina, is looking forward to improving her Arabic-language skills. "I wanted to come to AUC because it has a great reputation, and I want to improve my Arabic. I have wanted to travel to Egypt since I was a kid," she said. "Everyone has been so kind already, and my expectations going forward are to make many great and long-lasting friendships and to improve my understanding of the region."

Vebjørn Hole Uleberg, an international student pursuing a Master in International Management/CEMS, came to AUC because it is the only CEMS academic partner in Africa and the Middle East. CEMS, or the Global Alliance in Management Education, is also the only AUC program ranked by the Financial Times and The Economist. "I find Egypt — with its culture, language, and people — very interesting," he said. "AUC is also the only University in the MENA region that is part of the CEMS network, meaning that it must be of high quality while also giving a unique cultural experience."

Uleberg is also looking forward to "seeing and experiencing what Egypt is like, including learning Arabic, getting to know locals and traveling all over the country," he added.

Marissa Jean Haskell is joining AUC from the United States. She had previously studied abroad at AUC as an undergraduate student. "I loved being here and in Egypt so much that I was looking for an excuse to come back," she said. "One of the main reasons I returned to AUC is the quality of professors here. At AUC, it seems like every professor is a well-known scholar in their respective field, so I am excited to learn from such renowned professionals. I am expecting to not only substantially broaden my knowledge of education and global affairs but also take advantage of the opportunity to grow my international network."

Egyptian students are joining AUC from more than 12 governorates across the country, including Giza, Monufia, Beni Suef, Ismailia and Gharbia.

For freshman Marwan Gamea, one of the main reasons he applied to AUC is sustaining a reasonable balance between academics and cocurricular activities. Gamea's intended major is data science, which "is exclusively available at AUC."

Salma Omar, a freshman intending to major in graphic design, decided to join AUC for the balance that it offers between the quality of education and the cocurricular activities that allow her to find her passion in various fields. "I thought it would give me the best education and environment to thrive," she said. "I am looking forward to building a solid foundation for my future and enjoying college life while still learning about my passion."

Lama Khallaf is another freshman intending to major in electronics and communications engineering who has chosen AUC for its liberal arts education that would prepare her for a strong career. "I'm hoping to really enjoy the diversity of courses that are offered. Although I'm an engineering major, I still have interests outside my major that I want to be able to pursue," she said.

Fahad Muhammad Dankabo, a freshman intending to major in political science, expects to make the best use of his time at AUC on so many levels. "I want to be able to develop both academically and socially," he said. Dankabo was overwhelmed with the welcome he received from everyone since he joined AUC. "The peer leaders' dedication truly reflected on the three-day orientation. It was simply superb and worth emulating. Everything was well-coordinated and executed. What a way to set a high standard for newcomers. Thank you for making it easy for me to blend into my new family."