Ethical by Design

By Em Mills and Devon Murray

If you can't imagine a future without AI, you're not alone. AI has transformed countless aspects of daily life and will only get more influential, leading some to ask, "Is AI going to take over the world?"

Fears of robot overlords aside, a more pressing concern lies in whether AI can learn to address the systemic inequalities that shape our society and inform our data sets. Left unchecked, AI is doomed to replicate and amplify the prejudice reflected in dominant culture. What needs to happen to set AI on the right path?

We spoke with AI experts Mona Diab '92, director of Carnegie Mellon University's Language Technologies Institute, and Aliah Yacoub '18, AI philosopher at Synapse Analytics and founder of the publication techQualia, to understand the latest developments and challenges in the realm of AI and why it's important to incorporate ethics into tech.

Diab and Yacoub

Diab and YacoubMona, you've been working with AI for more than two decades. How have things changed over the years?

MD: Our field used to be a bit of a hidden secret until the boom in 2017 when we started seeing far more large language model technologies hitting the market. Now, with things like ChatGPT, those technologies have really taken over the narrative and are much more mainstream.

What are some of the challenges accompanying the AI boom?

AY: The most critical challenges that we're facing today are of an ethical and social nature. Instead of focusing too heavily on questions about AI displacing workers or killer robots taking over the world, we should direct our attention to the pressing issues of feminist AI, geopolitical exclusion, regulation issues, bias and more.

We also face particular sociopolitical obstacles that make AI usage complicated: Countries can't create regulatory frameworks at the same pace that the technology itself advances or even at the same pace with each other. In Egypt, this is amplified by certain structures and governance issues that make the regulation of responsible AI a real challenge.

MD: Take things like Alexa, Siri, Google Assistant and machine translation. Many people blindly assume that they can always be trusted, which is very scary. In general, Google Translate does a phenomenal job. However, if you translate a language that has a limited digital presence -- meaning how much information about the language is accessible for AI to pull from online -- then your technology is less than perfect and you can run into a lot of trouble. With the growing accessibility and dependence on these technologies, from basic translation to courtrooms, it's imperative that they have a built-in notion of responsibility.

How can we build more responsible, culturally sensitive AI?

MD: It starts with building talent. We talk a lot about computational and critical thinking in computer science programs, but what I'd like to add to this conversation is responsible thinking. We want the people working with these new technologies to come in with social responsibility in mind, as opposed to adopting it later as a remedial or reactive attitude.

That's why I came back to the university; it's where people begin to study and work with these technologies. The idea is to start students out already understanding and grappling with these dynamics from the get-go.

AY: Because AI has become a fundamentally interdisciplinary field, it's vital for experts across specializations -- particularly the social sciences -- to have a voice and lend their personal skill sets to the field. That's how we can develop responsible AI.

Can you give us some examples of social responsibility in AI?

AY: One example of this is Data Feminism, a feminist AI approach which aims to address the issue of biased data sets that perpetuate inequalities. In the tech world, women are grossly underrepresented in every stage of production, from the theoretical to the technical. Feminist AI seeks to incorporate an analysis of contextual knowledge, power relations and marginalized perspectives, helping us understand who AI systems represent and who they ultimately serve.

Another example of social responsibility is localizing AI content to bridge regional literacy gaps. At techQalia, we approach this by writing in an accessible and exhaustive way, avoiding confusing academic jargon and releasing all of our publications in English and Arabic.

MD: Translating sciences into other languages so that people can study in their native language. It's not about dispelling English as a central language for scientific expression but rather enriching the scientific landscape by unlocking people's creativity in their native languages. This way, we create new algorithms, approaches and technologies. It comes with the territory of diversity.

Why is it important for Egypt and the Arab world to get involved with these technologies now?

MD: Facilitating scientific innovation in Egypt and the Arab world will enable local communities to flourish economically and enrich the scientific landscape as a whole, helping to balance out inequality in who gets a say in tech development. Right now, Silicon Valley predominantly defines the value systems of large language models because they're the ones with the means to build these technologies at scale. This creates a level of hegemony that we need to remain cognizant of, particularly in the context of colonialism and imperialism.

AY: Right now, Egypt struggles with severe AI illiteracy. We are rarely ever early adopters of new technologies, which means we miss out on the benefits of adopting generative AI across industries like healthcare and education. Aside from missed economic opportunities, the fact that algorithms are not trained on Arabic data can also have dangerous repercussions on our sense of identity, reproduction of knowledge and representation in data sets.

"We talk a lot about computational and critical thinking in computer science programs, but what I'd like to add to this conversation is responsible thinking."

Mona, a large portion of your work has focused on expanding the understanding of Arabic in large language models. Can you tell us more about this?

MD: My work came to fruition at Meta in the context of social media. People don't commonly speak in Modern Standard Arabic. On social media platforms, they use their own dialect and vernacular, so a reductionist understanding of Arabic like MSA renders translation ineffective and inaccurate. I challenged Meta to account for these variations, leading to more effective translations, better user experience and easier recognition of hate speech. Translating Arabic is a microcosm of exploring how to push the boundaries of computer science as a technology.

I want to get involved in AI. Where do I start?

AY: It's never too early and never too late to get involved with AI. Most importantly, it's never unrelated to your studies, no matter what they are. We actually recently published an excellent resource in English and Arabic for students called techQualia Career Guide, which offers insight into jobs in AI based on different fields of study.

MD: I highly encourage students to seek out ways of participating in global initiatives around AI. I have an initiative called 60-60 that I would really love for people to join. You don't have to travel to be able to participate in most initiatives. You can partake in events, courses, tutorials and programs online that will give you the opportunity to build a global network.

Any final thoughts?

MD: I'm actually an optimist when it comes to this technology because at the end of the day, it is human agency that controls it. As much as we are good, the technology will be good and will be put to good use.

AY: It's very difficult to think of an area of human life or human experience that AI hasn't already transformed or is plotting to transform. It's essential to start now, from the very beginning, focusing on ethical development.

___

Diab studied computer science at AUC and completed her master's in computer science at The George Washington University and her PhD in computational linguistics at the University of Maryland, moving on to conduct postdoctoral research at Stanford University and serve in leadership roles at companies like Amazon and Meta. Diab's work combines linguistics and computer science to make AI-powered tools effective and inclusive, focusing on responsible AI.

Yacoub studied philosophy and political science at AUC and completed her master's in philosophy at the University of Groningen. Her work focuses on the ethics, science and implementation of machine learning AI algorithms within a broader social context. She strives to explain, inform and critique the workings and implications of AI using a philosophical framework.

Moussa presents Egypt's oral arguments at the International Court of Justice, February 2024, photo courtesy of Jasmine Moussa

Moussa presents Egypt's oral arguments at the International Court of Justice, February 2024, photo courtesy of Jasmine Moussa Moussa at AUC New Cairo, photo by Gihad Belasy

Moussa at AUC New Cairo, photo by Gihad Belasy

Dina Iskander, adjunct professor of voice and founder and director of the AUC Opera Ensemble, sings a Broadway tune and a tribute to David Llewellyn Hales (1957-2020), a musician, accompanist and coach who worked with students and ensembles at AUC, and as a reminder to stay strong during these challenging times.

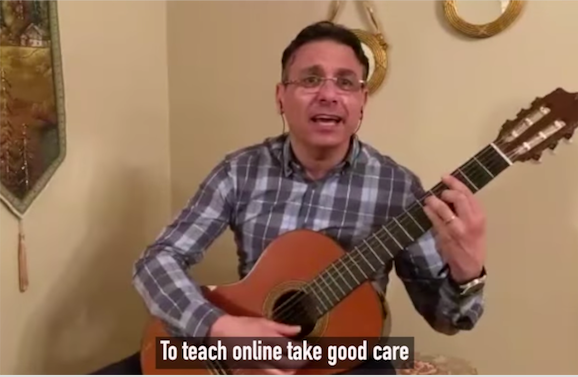

Dina Iskander, adjunct professor of voice and founder and director of the AUC Opera Ensemble, sings a Broadway tune and a tribute to David Llewellyn Hales (1957-2020), a musician, accompanist and coach who worked with students and ensembles at AUC, and as a reminder to stay strong during these challenging times. John Baboukis, professor and director of AUC's music program, initiated This is Not a Concert series to provide "musical comfort food" during the quarantine

John Baboukis, professor and director of AUC's music program, initiated This is Not a Concert series to provide "musical comfort food" during the quarantine Nesma Mahgoub '13, adjunct professor of voice at AUC, founder and director of A caPop choir and professional singer, sings Rise Up and I Dreamed a Dream from Les Miserables.

Nesma Mahgoub '13, adjunct professor of voice at AUC, founder and director of A caPop choir and professional singer, sings Rise Up and I Dreamed a Dream from Les Miserables.

"I am really delighted to be able to interact with my students and keep them going right from the first week of online teaching. Delivering the lectures during scheduled class time, using Blackboard Collaborate Ultra, allows students to be interactive by participating in real-time questionand-answer sessions." -- Abdelaziz Khlaifat, professor, Department of Petroleum and Energy Engineering

"I am really delighted to be able to interact with my students and keep them going right from the first week of online teaching. Delivering the lectures during scheduled class time, using Blackboard Collaborate Ultra, allows students to be interactive by participating in real-time questionand-answer sessions." -- Abdelaziz Khlaifat, professor, Department of Petroleum and Energy Engineering "The transition to online teaching has been smooth. Of course, there are challenges, but according to feedback from my students, they are satisfied. These are difficult times for us all, and we all have to come together and support each other by being understanding of how the disruptions to our daily routines have affected all aspects of our lives. I am thankful for how the AUC community as a whole has been very supportive." -- Adel El Adawy, assistant professor, Middle East Studies Center

"The transition to online teaching has been smooth. Of course, there are challenges, but according to feedback from my students, they are satisfied. These are difficult times for us all, and we all have to come together and support each other by being understanding of how the disruptions to our daily routines have affected all aspects of our lives. I am thankful for how the AUC community as a whole has been very supportive." -- Adel El Adawy, assistant professor, Middle East Studies Center "We don't always get the chance to work outdoors and enjoy the sun and breeze. This is an opportunity to make the best of the current circumstances. Stay positive, stay safe and stay home!" -- Caroline Mikhail (MA '14), executive assistant to the chair, Department of Computer Science and Engineering

"We don't always get the chance to work outdoors and enjoy the sun and breeze. This is an opportunity to make the best of the current circumstances. Stay positive, stay safe and stay home!" -- Caroline Mikhail (MA '14), executive assistant to the chair, Department of Computer Science and Engineering "I've discovered that making videos of my lectures is a great resource. Students tell me they like being able to rewatch any part they didn't catch the first time. I can tell from online responses that they are catching more of the content than they do taking notes in person." -- Elisabeth Kennedy, visiting assistant professor, Department of History

"I've discovered that making videos of my lectures is a great resource. Students tell me they like being able to rewatch any part they didn't catch the first time. I can tell from online responses that they are catching more of the content than they do taking notes in person." -- Elisabeth Kennedy, visiting assistant professor, Department of History "I gave my first online presentation through Zoom in the final course for the Professional Educator Diploma, and I rocked it! Keep it up, believe in yourself and stay safe." -- Islam Ahmed, School of Continuing Education student

"I gave my first online presentation through Zoom in the final course for the Professional Educator Diploma, and I rocked it! Keep it up, believe in yourself and stay safe." -- Islam Ahmed, School of Continuing Education student "The transition to remote teaching has been an overwhelming experience. We have gained a huge amount of knowledge in a very short time, and for that, I am extremely grateful. Distant learning is full of potential that is now smoothly implemented, and we will continue benefiting from it even after these hard times are gone." -- Mariam Abouhadid, adjunct assistant professor, Department of Architecture

"The transition to remote teaching has been an overwhelming experience. We have gained a huge amount of knowledge in a very short time, and for that, I am extremely grateful. Distant learning is full of potential that is now smoothly implemented, and we will continue benefiting from it even after these hard times are gone." -- Mariam Abouhadid, adjunct assistant professor, Department of Architecture "Working from home is definitely a new challenge for me, especially while having two kids around, but during these difficult times, we all have to stay home and stay safe so we can get through this together." -- Ragya Sorour, executive assistant to the chair, Department of Biology

"Working from home is definitely a new challenge for me, especially while having two kids around, but during these difficult times, we all have to stay home and stay safe so we can get through this together." -- Ragya Sorour, executive assistant to the chair, Department of Biology "Teaching online from home proved what I used to say to my trainees: 'Teachers will not be replaced by technology, but teachers who do not use technology will be replaced.'" -- Osama Sebaai, instructor and teacher trainer, School of Continuing Education

"Teaching online from home proved what I used to say to my trainees: 'Teachers will not be replaced by technology, but teachers who do not use technology will be replaced.'" -- Osama Sebaai, instructor and teacher trainer, School of Continuing Education "Working remotely is sometimes challenging, but it has definitely pushed me to find creative ways to maintain productivity. It also helps when my dog is by my side in every online meeting I attend. She is my support system." -- Suzan Kenawy '09, '20, marketing manager, AUC Press and Bookstores

"Working remotely is sometimes challenging, but it has definitely pushed me to find creative ways to maintain productivity. It also helps when my dog is by my side in every online meeting I attend. She is my support system." -- Suzan Kenawy '09, '20, marketing manager, AUC Press and Bookstores "These difficult circumstances enabled me to discover how patient, kind and understanding my professors are. Thank you to all AUC staff members who work in silence in order to ease our online journey." -- Samaa Abdelhamid, AUC student

"These difficult circumstances enabled me to discover how patient, kind and understanding my professors are. Thank you to all AUC staff members who work in silence in order to ease our online journey." -- Samaa Abdelhamid, AUC student "I am the corporate financial planning and analysis manager at PepsiCo headquarters in New York. I've got some work-from-home tips for everyone: Set a daily working hours timetable to be focused, dress up to freshen up, take refresh breaks every couple of hours, stay more connected with your teammates, organize a simple workstation and motivate your family members." -- Farah Haggag '10, '12

"I am the corporate financial planning and analysis manager at PepsiCo headquarters in New York. I've got some work-from-home tips for everyone: Set a daily working hours timetable to be focused, dress up to freshen up, take refresh breaks every couple of hours, stay more connected with your teammates, organize a simple workstation and motivate your family members." -- Farah Haggag '10, '12 "We graduated from the architectural engineering program in 2016. We just got our master's in urban design from The University of British Columbia in Vancouver, Canada. Now we are volunteering with an advocacy group called Car Free Day to apply what we have learned during our master's program in the city." -- Islam Ibrahim El Banna '16 and Aya Khaled Abdelfatah '16

"We graduated from the architectural engineering program in 2016. We just got our master's in urban design from The University of British Columbia in Vancouver, Canada. Now we are volunteering with an advocacy group called Car Free Day to apply what we have learned during our master's program in the city." -- Islam Ibrahim El Banna '16 and Aya Khaled Abdelfatah '16 "I graduated with a master's in international human rights law and a graduate diploma in forced migration and refugee studies in 2006. I have fond memories of my schooling at AUC. I am currently teleworking in Silver Spring, Maryland, as the deputy director of the Office of Conflict Management and Mitigation with USAID. When things calm down and travel is available again, I will be working for USAID in Khartoum, Sudan, as the deputy director of Food for Peace."-- Felicia Genet (MA '06)

"I graduated with a master's in international human rights law and a graduate diploma in forced migration and refugee studies in 2006. I have fond memories of my schooling at AUC. I am currently teleworking in Silver Spring, Maryland, as the deputy director of the Office of Conflict Management and Mitigation with USAID. When things calm down and travel is available again, I will be working for USAID in Khartoum, Sudan, as the deputy director of Food for Peace."-- Felicia Genet (MA '06) "COVID-19 has hit the United Kingdom hard, and little did we know that we will be staying home. I am a program leader for Further Education and Training at Edge Hill University. COVID-19 has shown us here in Liverpool the power of people coming together. The great Arab community in Liverpool and the Arabic center's initiative to provide food and support for families are exceptional. Liverpool is one of the beautiful cities in North West England that always makes me feel like I am in Alexandria or Port Said because of its waterfront and beautiful seas. Regardless of the current situation and remote work, I feel lucky to be able to hear the birds singing in the garden and see the occasional seagulls trying to steal some food." -- Shereen Hamed Shaw '06

"COVID-19 has hit the United Kingdom hard, and little did we know that we will be staying home. I am a program leader for Further Education and Training at Edge Hill University. COVID-19 has shown us here in Liverpool the power of people coming together. The great Arab community in Liverpool and the Arabic center's initiative to provide food and support for families are exceptional. Liverpool is one of the beautiful cities in North West England that always makes me feel like I am in Alexandria or Port Said because of its waterfront and beautiful seas. Regardless of the current situation and remote work, I feel lucky to be able to hear the birds singing in the garden and see the occasional seagulls trying to steal some food." -- Shereen Hamed Shaw '06

Outdoor classes might become a norm in the post-COVID world

Outdoor classes might become a norm in the post-COVID world